Despret's book is preceded by a foreword from Latour characterizing the purpose of this work as moving from a subtractive to an additive empiricism and challenging both what laypeople think they know about animals and the vociferous anti-anthropomorphism of the scientific community. Organized in a playful order with each question fitted to a heading for each letter of the alphabet, the book asks questions about what animals do and can do in such a way as to provoke the question: when can their behaviors be equated to human behaviors, and at what point can one reasonably assume equivalent thoughts or feelings? The essays also serve as commentary on the scientific processes that have told us what we know and given us the results we have, including unexpected discoveries about humans resulting from the effect of the experiments on the experimenters. Annotation ©2016 Ringgold, Inc., Portland, OR (protoview.com)

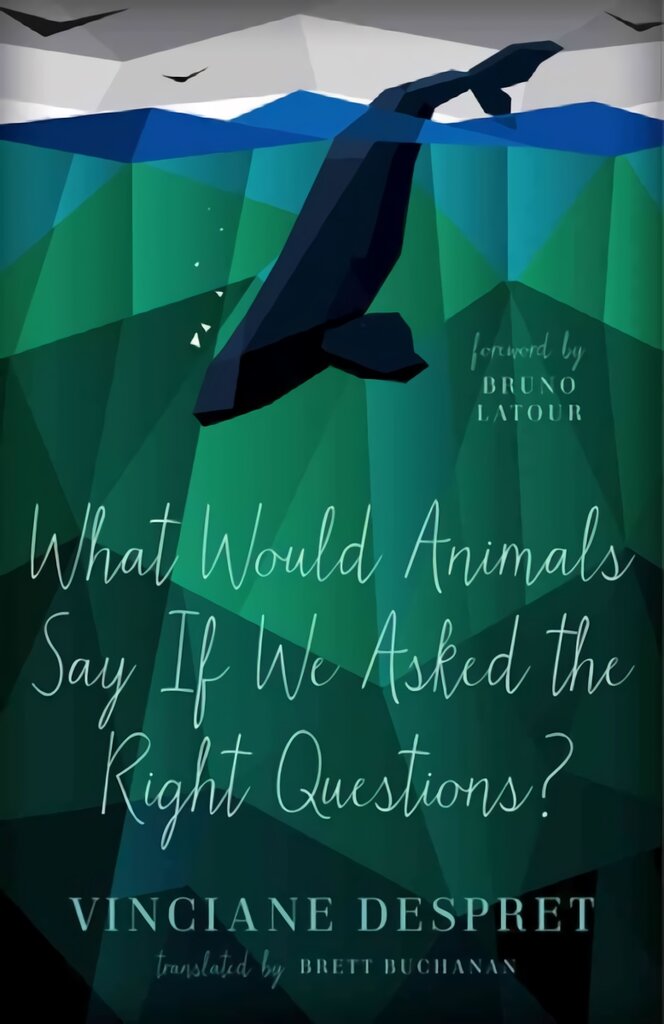

“You are about to enter a new genre, that of scientific fables, by which I don’t mean science fiction, or false stories about science, but, on the contrary, true ways of understanding how difficult it is to figure out what animals are up to.” —Bruno Latour, form the ForewordIs it all right to urinate in front of animals? What does it mean when a monkey throws its feces at you? Do apes really know how to ape? Do animals form same-sex relations? Are they the new celebrities of the twenty-first century? This book poses twenty-six such questions that stretch our preconceived ideas about what animals do, what they think about, and what they want.In a delightful abecedarium of twenty-six chapters, Vinciane Despret argues that behaviors we identify as separating humans from animals do not actually properly belong to humans. She does so by exploring incredible and often funny adventures about animals and their involvements with researchers, farmers, zookeepers, handlers, and other human beings. Do animals have a sense of humor? In reading these stories it is evident that they do seem to take perverse pleasure in creating scenarios that unsettle even the greatest of experts, who in turn devise newer and riskier hypotheses that invariably lead them to conclude that animals are not nearly as dumb as previously thought.These deftly translated accounts oblige us, along the way, to engage in both ethology and philosophy. Combining serious scholarship with humor that will resonate with anyone, this book—with a foreword by noted French philosopher, anthropologist, and sociologist of science Bruno Latour—is a must not only for specialists but also for general readers, including dog owners, who will never look at their canine companions the same way again.